Sometimes books raise questions. Sometimes books supply answers. A reader who pages through the picture book Mr. Reaper can be forgiven for asking: “Huh? What was the publisher thinking?” and arriving at the conclusion that allowing a popular and successful artist free rein is not always a good idea.

At its most basic, Mr. Reaper tells the story of a wolf who sets out to nurse a sick piglet back to health so that the wolf can eat him. The ending implies that the sacrifices that the wolf makes for his patient transform them into the best of friends.

At its most basic, Mr. Reaper tells the story of a wolf who sets out to nurse a sick piglet back to health so that the wolf can eat him. The ending implies that the sacrifices that the wolf makes for his patient transform them into the best of friends.

Unfortunately the bizarre decision to have Death narrate what should’ve been a simple and benign tale of empathy destroys whatever value and appeal it might have had. Instead of sweet and straightforward, the story is grim and garbled. Nearly every page shows Mr. Reaper spying on our characters while he repeatedly threatens them with imminent and capricious doom:

“The Reaper silently gazed at the two…In fact, you two will soon die.”

It’s not that death is an unsuitable subject for preschoolers. The University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Cooperative Children’s Book Center lists several books about grief and loss for children as young as three. Books such as Robie H. Harris’ Goodbye Mousie reassure children that death, while profoundly different from sleep, is just as natural.

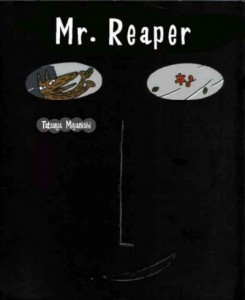

What’s wrong with Mr. Reaper is its overriding sense of foreboding and hopelessness. The black book jacket, die-cut to suggest two watching eyes, sets the harsh tone right from the bookshelf. Even though the final spread shows the former predator dancing with his erstwhile prey in a meadow, the flower heads that surround the dancers reinforce the reader’s feeling of being watched by an inescapable bully. It’s a confused and unearned “happy ending” that’s insufficient to undo the damaging message of the rest of the pages.

Mr. Reaper is the work of graphic designer and writer Tatsuya Miyanishi, who his many Japanese, French, Chinese, and Korean readers surely revere. Mr. Reaper, published in Miyanishi’s native Japan in 2010, was his first work to be released in English (in this charmless, dull, and unattributed 2012 translation). Given his obvious skill as an artist, one hopes that the dismal Mr. Reaper doesn’t kill Miyanishi’s chances with a U.S. audience.