Echoes of a distant childhood and a lost war everlasting…

From 1958 to 1963 I attended the parish school of the Saint Robert Bellarmine1 Catholic Church in Merrill, Wis. Although I forgot most of the experience, a few memories endured. One involved a book with a half-remembered title and a vague sense of nobility.

A half-remembered title and sense of nobility…

Why did I hang onto that particular mental scrap for so long? And why did it carry a positive association?

St. Bellarmine’s was a typical small town parish, oppressive in its alligence to dogma. My 7th- and 8th-grade years passed under the eye of a raptorial nun who called herself Constance. Sister Constance’s reputation as a disciplinarian remained more vivid than her ability as a teacher. That’s because her tool of choice was an 18-inch wooden ruler applied sharply to the palm of the hand, a device and a technique that our school’s namesake inquisitor would’ve sneered at.

This isn’t say that those years were without joy, in between paddlings. One routine that I remember fondly a half century later is this: Sister Constance reading to us as a class, daily I think, in a brief but welcome respite from her rigid schedule. Her book selection must’ve been mostly uninspired because later I could recall only a single title, and that imperfectly. But I still thought of it and kept searching from time to time…

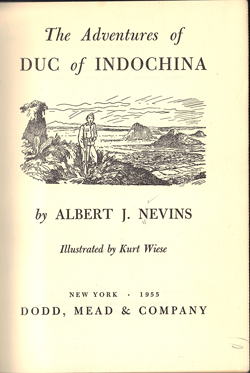

Decades later, it surfaced: The Adventures of Duc of Indochina. And I had to re-read it.

I admit that I was wary of Duc and his adventures, having been disappointed by other re-enacted memories. I feared that the book would turn out to be a clumsy and superficial capitalist or missionary screed. (After all, Sister Constance had a job to do in an era not far removed from “adopting pagan babies” and applauding Sen. Joe McCarthy.)

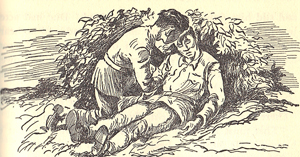

But after reading it, I’ve been amazed by the book’s many qualities. The story concerns teenage Duc’s attempt to save his family from the civil war waging around them in what is now called Vietnam. Failing that, he begins a two-year quest to reunite what remains of his family. Through it all, Duc is loyal to family and community and faithful to his ideals, which include a harmonious relationship between his own Christianity and his neighbors’ mixture of Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism.

Duc of Indochina is a well-researched, largely even-handed tale of innocent people destroyed by a political conflict they didn’t choose. The consequences of Duc’s loyalty to his village and its modest way of life, though unfair, are real and unavoidable. As Nevins puts it:

There were long rows of graves in the cemetery, and each tomb had a concrete slab giving the man’s name, his unit, and the date of death. There was one Vietnamese name after another, and under each name was the legend, “Mort pour la France” (Died for France).

“That is false,” Duc thought to himself. “Those men died for Vietnam, not for France! They did not die so that their children would be tenants in a house owned by a foreigner.”

The consequences, though unfair, are real and unavoidable.

Sure, author Albert J. Nevins dumps explanations into the narrative like overpacked duffel bags, but it’s usually only a paragraph or two at a time and, with at least one good fact per paragraph, that’s a good trade. Nevins also speaks with a formality that sometimes sounds corny to the modern ear, but is driven by his desire as a journalist to get the details right.

The Catholic clergy in the story are secondary figures, generally decent men with modest ambitions for themselves and their followers. The Vietminh rebels (precursors of the Viet Cong) come up for more criticism than their French-led opponents, the Vietnamese army. The former are cast as brutal, unempathetic ideologs while the latter “were spick-and-span, determined to show their fellow nationals that their army was capable of protecting the country and the people.” (Of course, President Diem2 taught us otherwise.

After excaping the Vietminh, Duc fights with the French at Dienbienphu. Their defeat there led to the surrender that ended France’s long occupation of the region. It also paved the way for the U.S. to step into that quagmire of death and destruction on its own. (Let us never forget how that turned out.)

Nevins, a Catholic priest, was not unbiased. He made his opposition to the Communist Vietminh clear, calling them “Red hordes.” But as a journalist, he respected his title character and came down squarely on the side of ordinary Vietnamese who wanted only to live their lives unmolested by political theory.

The Adventures of Duc of Indochina ends with the teenage Duc reuniting with the few family members and friends who survived, and fleeing with them to what became South Vietnam. Despite his personal suffering and loss, Duc remained undaunted as he looked forward.

“I see the blood and glory of a thousand yesterdays.”

“Can you see tomorrow?”

“No, Sap. That I cannot see.” Duc straightened up and put his hand on his friend’s shoulder. “We must make tomorrow.”

Duc’s lost world.

So that’s what I retained all these years: This fictitious stranger’s optimism made all the more poignant by the knowledge of what happened to his Vietnam after his story ends. Sister Constance might’ve intended to inspire us with a tale of Catholic fortitude, but what I got out of it was something simpler. Upon reflection, given my experience of a wooden ruler compared to weapons of war, I had a renewed appreciation of my own good fortune.

1 Among other duties, Robert Bellarmine (1542–1621) served Pope Clement VIII as a Cardinal Inquisitor. In that position, Bellarmine defended the faith against heretics up and including execution and helped persecute Galileo Galilei. We students were oblivious of this background. If we had known, of course, our budding adolescent sarcasm would surely have been merciless. Return

2 Nevins, writing in 1955, characterized South Vietnam’s first president, Ngo Dinh Diem, as “an honest Nationalist.” However, like Robert Bellarmine, Diem was not what he seemed. Also a Roman Catholic, the new president proved to be remarkably corrupt and went on to oppress followers of other religions, eventually making enough enemies to be deposed and assassinated. Return