Safe in an armchair, contemplating Nature, red in tooth and claw…

I was raised in a community that considered hunting for food to be as natural as driving a car or tractor. I didn’t hunt, but I knew the basics of gun ownership. As a kid I even once qualified for the National Rifle Association’s basic marksmanship certificate (way back when the NRA was primarily a gun safety organization).

Similarly I never owned a dog in my youth, but I knew what it was like to be around dogs, to have them underfoot, and making noise, and nosing in the grass for something to eat and then roll in.

Similarly I never owned a dog in my youth, but I knew what it was like to be around dogs, to have them underfoot, and making noise, and nosing in the grass for something to eat and then roll in.

I don’t remember how I discovered Jim Kjelgaard, or which of his nearly 50 juvenile books I read first. Big Red is the one that sticks in my mind, although when I re-opened it for the first time since the 1960s, I didn’t remember much plot or character detail. What did surprise me was how quickly the book drew me into the adventure of a seventeen-year-old Danny Pickett and his champion Irish setter. Surprising, mostly because Big Red features the kind of stirring, archaic prose that might’ve inspired a young Teddy Roosevelt:

Any mongrel with four legs and the ability to run could hunt varmints. Danny looked fondly at the big setter. The first man who had dreamed had dreamed of a dog to hunt birds, and to make Red a varmint dog would almost be betrayal of that man and all the others who had striven to make the breed what it was.

What makes this potential fustiness go down so well is the homely speech of the outdoorsmen who live harmoniously in Kjelgaard’s imaginary wilderness:

Ross [Danny’s father] gulped, and then grinned. “Don’t even trouble your head about me. I’m no tenderfoot deer hunter, as has to git his game the first day or he don’t git it.”

The result is an adventure on the scale of Treasure Island or Captains Courageous.

Like them, Big Red is firmly a chronicle of its time–earnest and epic.

Like them, Big Red is firmly a chronicle of its time–earnest and epic.

Tellingly, the animals in Danny’s world are heavily anthropomorphized. Danny lives in a world were “monster bears” exhibit “customary cunning”:

The savage, silent, head-swinging bear still roamed the Wintapi, an implacable, hating enemy of all the humans who trod there.

Kjelgaard’s vivid images can stop a reader in his tracks with their precision: “A couple of crows cawed raucously from the top of a beech, and flew on the devil’s business that their kind are always about.”

Crows have their place, however, as does all life. The book presents class hierarchy as an unquestionable given. Danny calls the wolverine that raids his trapline an “Injun devil” with provincial thoughtlessness. And Danny and his father live “by the grace of Mr. Haggin” on the wild edge of their wealthy patron’s “carefully nurtured” estate.

![]() The book is unabashedly masculine. Its only female character is one of Mr. Haggin’s managers, a “quality woman” visiting from Philadelphia who commits the cardinal sin of valuing Red only as a decorative possession. The bulk of the remaining 200-plus pages focusses on the important manly concerns of trackin’, trappin’, skinnin’, shootin’, fightin’, and rustlin’ up some hearty grub.

The book is unabashedly masculine. Its only female character is one of Mr. Haggin’s managers, a “quality woman” visiting from Philadelphia who commits the cardinal sin of valuing Red only as a decorative possession. The bulk of the remaining 200-plus pages focusses on the important manly concerns of trackin’, trappin’, skinnin’, shootin’, fightin’, and rustlin’ up some hearty grub.

Yet for all the shortcomings of its age, Big Red is still worth reading.

Big Red is a detailed catalog of outdoor craft. Danny is an excellent woodsman, whether bleeding a dead bull (one of the bear’s victims) to preserve its meat for the landowner, or outwitting a bear on the run. Even the book’s exaggerated anthropomorphism is grounded in a detailed knowledge of animal behavior that makes its many descriptions pulse with life.

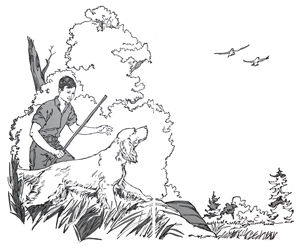

And a young reader could do a lot worse for a role model. Red’s journey from raw potential to disciplined perfection is the result of Danny’s fundamental kindness and unwavering vision.

Ross scoffed at the notion that a whipping would hurt him, but Danny knew better. Red had depths of feeling a sensitivity that he had seen in no other dog, and he was proud, He wouldn’t bear the lash any more than would a proud man.

Danny’s trust pays off. In maturing, Red’s good nature blooms, as does his selfless courage in defending his beloved Danny from the mortal threats that lurk in the wilderness. Their united battle to defeat the marauding bear provides the ultimate measure of their partnership.

Danny’s trust pays off. In maturing, Red’s good nature blooms, as does his selfless courage in defending his beloved Danny from the mortal threats that lurk in the wilderness. Their united battle to defeat the marauding bear provides the ultimate measure of their partnership.

The best way to appreciate Danny Pickett as a protagonist it to compare him to his fictional contemporary, the far more well known Holden Caulfield. That famously cynical, rude, superficial, selfish, narcissistic twit is Danny’s antithesis.

In contrast, Danny embodies the highest traits of his species–smart, hard-working, uncomplaining, generous, and brave. The kind of honorable young man who deserves the hero worship of the noblest of dogs and the most jaded of contemporary readers.