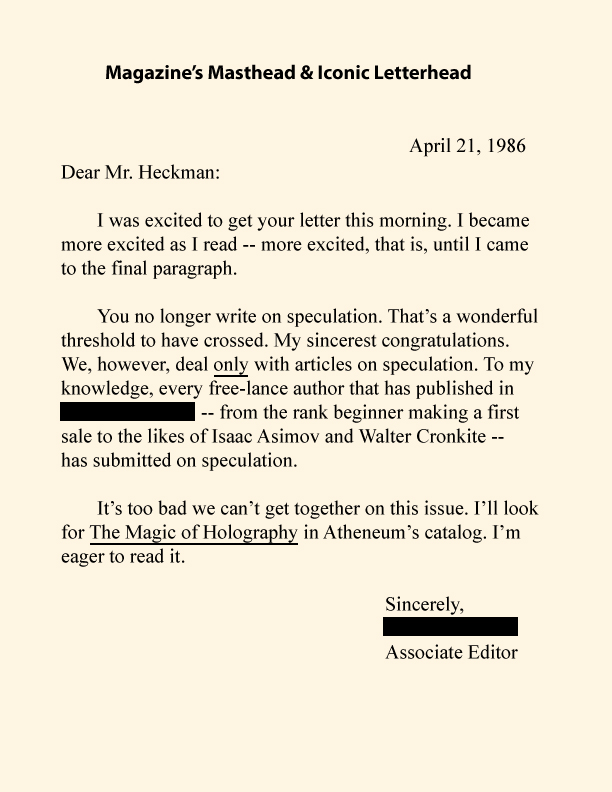

As a writer, I’ve received my share of rejection notices. My favorite, for its pointed sarcasm, came my way after I tried to bluff the submissions editor of a national children’s magazine. Here’s the smackdown:

Tag Archives: writing

Forgotten books: The Garden Under the Sea

On the shoreline, preparing to cross between pairs of worlds…

I don’t recall when I first heard the melody of “Sweet Molly Malone,” but I’m certain where I first read the lyrics:

She wheeled her wheelbarrow

Through streets broad and narrow

Crying, “Cockles and mussels

Alive, alive ho.”

The tune comes to mind unbidden, often when I’m working outdoors, bringing with it a pleasant melancholy, the emotional residue of a book that I received from my parents when I was eight or nine. The Garden Under the Sea (by George Selden) might seem an unusual present for a child for whom the nearest seaport was Milwaukee, but considering its lasting influence, it represents gift-giving genius.

The tune comes to mind unbidden, often when I’m working outdoors, bringing with it a pleasant melancholy, the emotional residue of a book that I received from my parents when I was eight or nine. The Garden Under the Sea (by George Selden) might seem an unusual present for a child for whom the nearest seaport was Milwaukee, but considering its lasting influence, it represents gift-giving genius.

The premise of The Garden Under the Sea is simple: A contentious lobster named Oscar uses questionable means to fight an injustice. The basis of the conflict is the tendency of the humans who each year descend on the Long Island shore to decorate their cottage gardens by “Shell stealing, glass stealing, rock rearranging, and general ruining of the ocean floor.” Tired of losing debris that the neighborhood’s aquatic residents consider the sea’s rightful property, Oscar rallies them to retaliate. Thus begins a summer of beach blanket stealing, sandwich stealing, and general raiding of assorted treasures left unattended above the waterline.

The Garden Under the Sea is an unusual children’s book by contemporary standards. With its sophisticated language and genteel anthropomorphism, it follows the tradition of Kenneth Grahame’s Wind in the Willows, especially its seventh chapter, “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn.” The moral guide of The Garden Under the Sea is a “wise old periwinkle,” who cites maritime traditions with Nor’eastern aplomb: “It ain’t what you salvage,” said the periwinkle sternly, “It’s how you salvage it. If you go at it with respect for what”s been wrecked, and pity for the people involved, that’s one thing. If you don’t, that’s anothah.”

The plotting that goes into building the underwater garden plot yields a plot that’s episodic rather than overarching. Still, the book’s recurring narrative tides memorably convey humans’ persistent inability to embrace their environment. Ultimately our efforts to comprehend and live in harmony with the world come up short, leaving us with “a great Awe.”

The next morning–not quite at six o’clock–Howard and Janet came down to move their meteorite. When they couldn’t find it, they called their mothers and fathers and they came down too. Soon the whole neighborhood was scouring the beach. One group held that the tide had washed it away; another said that shooting stars always evaporated after they hit the earth. But Howard and Janet didn’t believe either of these theories. It was a puzzle , and they admitted it. As a matter of fact, it was just one of several things that happened that summer on Crescent Beach which the human beings living there never did fully understand.

The Garden Under the Sea was published in 1957, three years before author George Selden‘s more well-known book The Cricket in Times Square. Perhaps overshadowed by that Cricket‘s Newbery Honor award, The Garden Under the Sea doesn’t deserve to be forgotten. Through its descriptions of storm and shipwreck, meteorite fall and fireworks, it shows how the the man-made and natural worlds parallel each other in confounding wonders whose power to enthrall remains forever alive, alive ho.

Railing against imperfection

For most of my editing career, I relied on typesetting professionals to copy fit and make text changes. Each round of editing generated a new proof, which often led to further changes.

The artists and typesetters I worked with were unfailingly gracious with my repeated attempts to “perfect” a story with corrections I thought essential. However, they made it clear that three proofs should be enough to finish the job. My asking for Proof #4 was pushing our friendship. Proof #5 was stretching the social contract between us. And as for Proof #6, well, I better bring doughnuts.

As a result, far too many imperfect articles left my hands because I finally ran out of the nerve to beg an artist to provide one more missing comma.

Not so with self-publishing. If I were counting “proofs” for this post, I’d hit double digits trying to correct every last imperfection. Online, I could–and would–always be willing to make another change.

So it’s especially frustrating when, in regard to non-editorial projects, I’m prevented from fixing that “one more thing.”

Take the new kitchen railing I recently installed. I ordered the parts from a local custom builder, and spent the better part of a day putting it up. (Never having done this before, it was measure 10 times, drill once. Oh yeah, and go to the hardware store twice.)

After seven hours, I was worn out and willing to overlook a number of imperfections that I was sure no one else would notice. (Can you tell how the ends of those balusters aren’t perfectly flush with the floor?) So I didn’t pay as much attention to the final step as I wish I would have.

See where the railing attaches to the wall? In my haste to finish the job, I drove nails through that oval rosette without aligning its wood grain vertically. As you can plainly see, the rosette is 6 degrees from the perpendicular.

Big deal, you say. But it’s forever. I can’t fix it, not without risking major damage to the wall or the rosette, or both.

So now I’m reminded of the flaw every time I use the stairs. As many as a dozen times a day, I’m mocked by my failure and forced to face the truth that all that stands between the job as it is and perfection is the equivalent of a Proof #21. And alas, that ain’t gonna happen.

Such is the degraded life of an former editor, thwarted by reality.

Why I procrastinate

Why do I procrastinate? I’ve been wondering for some time.

Why do I procrastinate? I’ve been wondering for some time.

I’ve long wanted to write a personal Hesitancy Manifesto, but I kept putting it off. I guess I wasn’t ever quite ready, or maybe I was ready but still asleep.

I rationalized that creating a formal declaration of delay implied that I didn’t take the principle seriously. Let’s face it, few people do. Procrastination is not held in high regard. Take Major General George B. McClellan. Take Hamlet.

People assume that procrastinators can’t pull the trigger because they fear failure. But it’s not that simple. Sure maybe you don’t ask someone out because you’re afraid of being rejected. But suppose that person accepts your offer–what good is that? Acceptance means you can’t go out with other people equally or even more desirable. Why rule out all those exciting unknown prospects by picking just one?

No, it’s not that I’m afraid to fail. It’s that I won’t settle for a single consequence.

Considering all the alternatives, no matter how remote, procrastination is only logical because procrastination is all about preserving possibility. For an architect, say, it’s easy to imagine a house of many shapes, sizes, and styles before the foundation is dug. As long as she doesn’t think too specifically about working, or start working, or actually work, she can build anything. And as long as she has yet to act, the possibilities are endless and every imaginable outcome presents unlimited promise.

To choose a course and act on it is to set all other courses aside. Until I lay down my first word, all sentences are available to me. So I procrastinate to preserve my maximum potential. As long as I hold off word smithing, I can prolong the pleasure of anticipating what I will write. And when that day comes when I do succumb to the urge to string letters together…

Why, then, the work’s mine oyster, Which I with word will open.

In the meantime, all that latent award-winning writing? I know I have it in me.

Heard any good voices lately?

Readers finish books because they want to know what happened. Readers start books because they find the storyteller appealing.

Most readers make the decision to proceed with a book within the first few pages, usually before the plot gets going. And what evidence do readers have to go on? Only the narrator’s voice, the trickiest element of storytelling.

Here’s my favorite example of a voice that demands attention:

People do not give it credence that a fourteen-year-old girl could leave home and go off in the wintertime to avenge her father’s blood but it did not seem so strange then, although I will say it did not happen every day. I was just fourteen years of age when a coward going by the name of Tom Chaney shot my father down in Fort Smith, Arkansas, and robbed him of his life and his horse and $150 in cash money plus two California gold pieces that he carried in his trouser band.

The plot details in this opening paragraph of True Grit are incidental. More important is the fact that in these first two sentences author Charles Portis deftly conveys his narrator’s basic character–her morals, intelligence, and determination–and we fall in love with her at once. With the sound of Mattie Ross’ voice, we instantly commit to her tale. Her voice makes us believe, respect, and root for her. There is no way to turn away from her story after we hear her speak.

The plot details in this opening paragraph of True Grit are incidental. More important is the fact that in these first two sentences author Charles Portis deftly conveys his narrator’s basic character–her morals, intelligence, and determination–and we fall in love with her at once. With the sound of Mattie Ross’ voice, we instantly commit to her tale. Her voice makes us believe, respect, and root for her. There is no way to turn away from her story after we hear her speak.

I believe creating a narrative voice that is credible and compelling is the writer’s single greatest challenge. Plot isn’t worth a damn unless we give a damn about the storyteller. The voice we hear on page one better be someone who sounds interesting. After all, he or she is asking to live inside our heads for a while.*

What is your favorite narrative voice–the one that sold you on his or her story from the very first sentence?

* By the way, the same point applies to nonfiction. Even some textbooks are more readable than others because of the writer’s voice.

Joseph Grand and the horse he rode in on

Joseph Grand is a character in The Plague, by Albert Camus, a slim but inspiring novel bounced from liberal arts reading lists by the ruthless obsolescence of relevance. The story takes place during an epidemic in 1940s Algeria. Grand is a civil servant, distinguished by his colorless fulfillment of duties and his obsession with writing a perfect novel, a work of art of such obvious quality that:

“On the day when the manuscript reaches the publisher, I want him to stand up— after he’s read it through, of course—and say to his staff: ‘Gentlemen, hats off!'”

Unfortunately, Grand can’t get past the first sentence. His ideals don’t allow him to move forward until the text is flawless. As he puts it:

“I grant you it’s easy enough to choose between a ‘but’ and an ‘and.’ It’s a bit more difficult to decide between ‘and’ and ‘then.’ But definitely the hardest thing may be to know whether one should put an ‘and’ or leave it out.”

At one point, Grand’s opening reads:

“One fine morning in May a slim young horsewoman might have been seen riding a handsome sorrel mare along the flowery avenues of the Bois de Boulogne.”

As soon as he solves one problem–the substitution of “slim” for “elegant” say–another crops up. It’s “handsome” this time, which he believes doesn’t paint a clear enough picture. He rejects “plump” as demeaning and vulgar. He discards “beautifully groomed” as awkward.

Then one evening he announced triumphantly that he had got it: “A black sorrel mare.” To his thinking, he explained, “black” conveyed a hint of elegance and opulence.

“It won’t do,” Rieux said.

“Why not?”

“Because ‘sorrel’ doesn’t mean a breed of horse; it’s a color.”

“What color?”

“Well—er—a color that, anyhow, isn’t black.”

Grand seemed greatly troubled. “Thank you,” he said warmly. “How fortunate you’re here to help me! But you see how difficult it is.”

Well said, my muse. Only you would understand how many times I previewed this post before publishing.

Opening for a YA novel I’m working on

It had been a while since I’d worked on a YA novel about a boy confined to his apartment building for the summer. When I ran across this draft opening paragraph I decided it was time to return to the story.

My mother, Abigail Wilson Secrest, doesn’t like the idea of

me watching violence on TV. So I make sure she doesn’t find

out.I remember this old movie I saw once. Cowboy is sitting in

a saloon alone, drinking a glass of beer. Bad guy walks in and

starts drinking and complaining. Says to the dancing lady: You

know what I hate? I hate this town, it’s dirty and it stinks.Drinks some more and says to the bartender: You know what I

hate? I hate this rot-gut whiskey of yours. It tastes like the

Pecos River after a herd of cattle went through.Drinks some more and says to the cowboy: You know what I

hate: I hate your ugly face. And the bad guy pulls out a gun

and waves it at the cowboy. What do you got to say to that? he

says. And then the bad guy puts the gun under the cowboy’s

chin. Answer me, he hollers at the cowboy, or I’ll blow your

head off.Next thing, the cowboy’s gun goes off from under the bar

and the bad guy flies backwards through the air dead. Cowboy

puts his gun on the bar and says to the bartender: You know what

I hate. I hate a man who needs help shutting up.Let me tell you what I hate.